‘Ye are Blood of my Blood, and Bone of my Bone.

I give ye my Body, that we Two might be One.

I give ye my Spirit, ’til our Life shall be Done.’

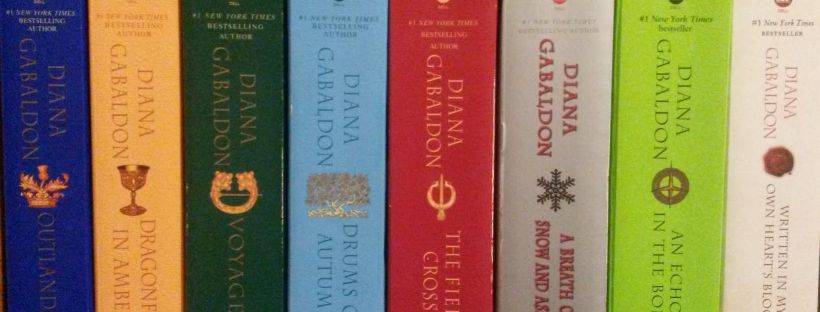

Even a casual fan recognizes these words as the vows that wed Jamie and Claire Fraser in Diana Gabaldon’s 1991 novel Outlander. The first Outlander novel is billed as a sexy historical fantasy, starring an unfaithful heroine and too-good-to-be-true hero. But between sensationalist sex and a controversial spanking scene, Gabaldon lays the groundwork for what becomes an intricate historical epic. By the eighth novel, Written in My Own Heart’s Blood, the series has grown far past its humble beginnings. I don’t want to completely discredit the first book in the series, because if I hadn’t loved it so much I would have never read the rest, but Gabaldon managed to take her freshman novel and turn it into something truly unique. As I got to know the family of the Fraser-Mackenzie-Wakefield-Murray-Randall-Greys, I found something that I loved, a depth of character and setting which felt bizarrely familiar and real. The heart of Outlander is found in these wedding vows, in the oaths and promises that make a family out of strangers. The series’ time travel and hereditary powers are not just fantastical elements, but also symbolic of the core story – blood finding its blood, across space and time. Beneath all of the sex and drama that made Outlander popular, the story is a familial epic driven by the tension between biological lineage and found family.

I don’t know how to start analyzing a series that has a word count of almost 4 million words. But I need to start somewhere, so we’re starting with Claire. Claire Beauchamp is an orphaned child, born in 1918 and raised by her uncle with no other family to speak of. She marries Frank Randall, but after only months of marriage they are separated by WWII. Frank is obsessed with his ancestors. He also seems to have no living family, which only strengthens his interest in his past. He wants a child – a Randall – but none come. Frank and Claire are united by marriage vows, but neither has any roots, any investment beyond love. The couple goes on a quiet vacation to Inverness when the war is over, looking for a “peaceful refuge in which to rediscover each other” (Outlander 1). Claire and Frank’s rootless marriage is at a tipping point – a point of recommitment. And it’s in this moment of unbalance that Claire disappears through a fairy circle, 200 hundred years into the past. The displacement in time leaves her again an orphan. It is not immediately obvious to the reader, but Claire was not simply torn from her own era into the chaos of the 1740s. Claire had no home. It was waiting for her on the other side of the fairy circle.

James Fraser is the man waiting on the other side, the man who becomes her second husband and the father of her two children. James, nicknamed Jamie, was born 1721 in northern Scotland. Youngest child of Laird Brian Fraser of Lallybroch, Jamie loses his mother and older brother early in his life. The loss of his brother meant that Jamie would inherit the small estate, and more importantly, be responsible for the families who live and farm on the Fraser land. But after an altercation with the English army, started when Jamie tried to “defend(…) my family and my property,” Jamie’s future changes again (5). He is beaten and imprisoned in Fort William and escapes with a price on his head. He has to leave his estate in the hands of his sister following the death of his father. He changes his name and goes to live in exile with his maternal uncle’s clan, the Mackenzies. When we first meet Jamie, he is living as a stable boy under the name McTavish, alienated from his sister, his people, and his lands.

Jamie and Claire marry under strange circumstances, but by the end of the first novel, Claire has found a home with him. They return to Lallybroch – to his family. Claire finds a sister and brother in her in-laws, Jenny and Ian. She meets the families who live on the land where she is now Lady Broch Tuarach. 200 years away from the 20th century, Claire is rooted into a family like she never was in her own time. At this point Claire still believes she might be infertile, but she is hopeful, saying she “wouldn’t choose” not to have children (33). And now there is something bigger for a child to be born into. Any child of hers could inherit Lallybroch. For Jamie, a continuance of the Fraser lineage is important not just personally like it was for Frank, but because there would be so much for that child to have.

Jump forward three years. Claire and Jamie have lost a stillborn daughter, Faith. Scotland is on the brink of war with England. Claire, pregnant with her second child, has a choice to make: stay in Scotland and face the war, lose another child due to primitive medicine, and lose her husband in one of the bloodiest battles in history, or go back to Frank. Jamie signed over the deed of Lallybroch to his nephew, giving up hope of his blood lineage continuing in his family home. Their unborn child would no longer have anything to be born into – just war and chaos. The day of Culloden, Claire gives up her new family to save her daughter’s life. She goes back to the 20th century. This time Claire is not just leaving behind a husband. She is leaving a sister, nephews and nieces, her foster son Fergus, and Faith’s grave.

In the interlude, Claire and Frank raise the baby Brianna – blood of Jamie Fraser, the heir apparent of Lallybroch. Claire spends twenty years displaced in time again, physically in her own time, but emotionally orphaned once more. “I had the worst of the bargain,” Claire says to Bree when she’s older. “We lived, you and I, because he [Jamie] loved you” (Dragonfly 47). After Frank’s death, Claire finds out that Jamie survived Culloden. She tells Bree the truth and prepares to return to the 1760s. Claire goes back to her roots, to what was her real family. Over the course of their marriage, Jamie and Claire collect orphans and runaways who they love and support like their own. Jamie and Claire’s 20 years apart changes their perspectives. Neither thought they would ever see each other again, let alone be able to continue to grow their family. The Frasers use their second lease on marriage as generously as they can, taking in the unwanted, rescuing the abused, parenting and loving to make up for the years they lost. In the most recent novel Claire is 62 years old with six grandchildren in 1779. A far cry from the orphan displaced in time, time travel gave her her life.

In the interlude, Claire and Frank raise the baby Brianna – blood of Jamie Fraser, the heir apparent of Lallybroch. Claire spends twenty years displaced in time again, physically in her own time, but emotionally orphaned once more. “I had the worst of the bargain,” Claire says to Bree when she’s older. “We lived, you and I, because he [Jamie] loved you” (Dragonfly 47). After Frank’s death, Claire finds out that Jamie survived Culloden. She tells Bree the truth and prepares to return to the 1760s. Claire goes back to her roots, to what was her real family. Over the course of their marriage, Jamie and Claire collect orphans and runaways who they love and support like their own. Jamie and Claire’s 20 years apart changes their perspectives. Neither thought they would ever see each other again, let alone be able to continue to grow their family. The Frasers use their second lease on marriage as generously as they can, taking in the unwanted, rescuing the abused, parenting and loving to make up for the years they lost. In the most recent novel Claire is 62 years old with six grandchildren in 1779. A far cry from the orphan displaced in time, time travel gave her her life.

These days, time travel makes one think of sci-fi, but there is nothing scientific about the portals in Outlander. Even as the characters try to understand the rules of the portals, they can’t know more than what they discover through trial and error. Diana Gabaldon’s time travel is magic, plain and simple. She uses the time travel to explore displacement and adopted family while the biological predisposition needed to use time travel ties the story back to the importance of inherited familial traits as well. As we continue to learn about the laws of time travel in Outlander, there seems to be one steady rule: there has to be something waiting for you on the other side. Travel is easiest and safest when you know where you are going, and who you will find.

There are many travel theories, including the more violent ones that note that “fire and blood were necessary” for safe travel (49). There are multiple portals – in Scotland, France, North Carolina, Jamaica. Most of the time-traveling characters use gemstones as protection, an old theory from the mysterious characters of Geillis Duncan and Master Raymond. But much of the time travel is done in faith, as characters desperately try to find someone on the other side. When Bree stepped into the stone circle in the 1960s to find her parents, she had no plan or protection, just love driving her. But there are also times when a character doesn’t know where they’re going to – but the stones do. The most obvious example is Claire’s first trip, when the stones brought her unwittingly to Jamie. But there are other instances when the magic tries to unite families in its own way. For instance, in the eighth novel, Roger (Bree’s husband) travels back in time, trying to find his missing son. But the stones bring him back to Northumbria instead to find his father, who Roger, orphaned as a toddler, could barely remember.

The ability to time travel is a hereditary trait. Claire has it, her daughter and son-in-law have it, and her grandson has it. This biological trait allows the characters to move from era to era, creating one family from two centuries. But the blood that binds Claire’s family together causes a divide between those who can and can’t travel. Jamie can’t time travel, and neither can their adopted son Fergus or his family. When Bree and Roger need to return to the future for their daughter’s health, their young son Jemmy doesn’t understand why his cousins can’t come along. Claire can not bring her entire family to the safety of the 20th century. Those “adopted” into the Fraser family cannot share the experience of time travel. There is a scene at the end of The Fiery Cross when the family has to face the truth of who can and can’t travel. Those who can can “hear the voice of time,” a roaring sound near the portals, and when handling the gemstones that assist the journeys (109). “Why is it that you can do… what ye do, and Uncle Jamie and I canna?” asks Claire’s nephew Ian. “It’s genetic. It has to be,” Claire says (109). Genetics and dominant genes are constant themes in the series, as Claire uses examples like rolled tongues and eye color to try to understand the ability that half her family has.

“Blood of my blood” oaths can only bind two people so much. As much as Outlander is a story of finding family against all odds, there is still a distinct difference between Claire’s blood and Jamie’s. When Jamie asks his son-in-law if they are planning to return to the 20th century, after finding out that Roger and Bree’s son can travel, Roger says, “I am still thinking… m’ athair-cèile. (…) I will stand by you. We will stay” (109). Roger and Bree are forced to return to the future later in the series, but the disconnect between the world they were born into and the world where their adult lives began is too much, and they return to the dangers of the past, for the sake of their family. When there is a chance that Claire might have to return to the 20th century, Jamie says he is “not brave enough to live without [her] anymore” (A Breath of Snow and Ashes 120). Claire chooses to stay. As her family grows, the thought of leaving becomes more impossible. Eventually, it isn’t even a question anymore. The past is her present. There is nothing on the other side.

Outlander’s parallel themes of adoption and bloodlines manifest themselves most obviously in the parallel lives of Brianna and William. Brianna is Jamie’s daughter, a Fraser, born in 1948 in Boston, raised by Frank Randall as her father. William is also Jamie’s son. Born in 1758, William was conceived during the 20 years Jamie spent without Claire. William’s mother coerced Jamie into sleeping with her, before her arranged marriage to the earl Ludovic Ranson. William’s mother and legal father died when he was still a baby, and he was raised by Lord John Grey in England, legally the 9th Earl of Ellesmere, completely unaware of his true parentage. Brianna and William bring together the conflicting themes of adoption and preservation of bloodlines, as the half siblings are raised separately in separate centuries by foster fathers (Frank and John) who could not further their own blood lines.

Frank, as was said before, was infertile. His only child was Brianna, who he raised as his own despite knowing she was not his. Bree looks like Jamie, with his “lean height” and “ruddy hair” (109) and Frank spent 20 years looking at his wife’s other husband in his daughter’s face. Frank, who so desperately wanted his own child, never had one, and his Randall line died with him. Even though he raised Bree and claimed her as his own, Bree is the blood of Jamie’s blood, and the biological furtherance of the presumed-dead Fraser line. Similarly, William was raised by Lord John Grey, a gay nobleman with no hope or desire to further his biological line. William is also a Fraser, and also resembles Jamie. More so, he resembles his sister. “Dear God, they were alike” thinks Lord John the first time he see them together as adults. “The small tricks of expression, of posture, of gesture” (Breath of Snow and Ashes 118). Lord John and Frank both loved their adopted children as their own, but they were also painfully aware that the children did not belong only to them.

While his two biological children were being raised by men who would never have their own, Jamie was on the run in Scotland. His lands and title were given over to his nephew, James Murray. Jamie lived with no hope of lineage because he had no legal parenthood over either of his biological children. For 20 years, he believed he would never even meet his daughter by Claire – he didn’t even know if they survived. But there is redemption in Outlander, and Brianna and William eventually find their father. When one character first sees Bree and Jamie together they think, “It was one thing to have been told that Jamie Fraser resembled his daughter. It was another to see Brianna’s bold features transmuted into power by the stamp of years” (The Drums of Autumn 55). There is also redemption for Jamie’s lost estate and title. Bree, Roger, and their children live in Lallybroch temporarily in the later novels. Even though the estate is two hundred years older than it was in Jamie’s time, his daughter and direct descendants are able to reclaim the house, despite his giving it up in 1746.

Since Brianna and William were not just raised apart from their birth father, but also completely ignorant of his existence, it makes the slow discovery of their blood ties all the more precious. For Jamie, who does not get to know his children until their adulthoods, it is a miracle. “What a mystery blood was,” Jamie thinks. “How did a tiny gesture, a tone of voice, endure through generations like the harder verities of flesh? He had […] accepted without thought the echoes of parent and grandparent that appeared for brief moments, the shadow of a face looking back through the years” (44). Brianna and William are the heart of the Outlander series, toeing the line between loving their adoptive fathers, who they believed were biological, and their true blood family found later in life. “He’s your son,” Brianna says to Lord John. “You’ve raised him all this time. […] William will never stop loving you. It was the same for me – when I found out about Da. I didn’t want to believe it at first; I had a father, and I loved him, and I didn’t want another one. But then I met Da… But I have never forgotten my other father“ (A Breath of Snow and Ashes 118).

Jamie and Claire’s story of redemption is a story of parenthood. Jamie suffered for many years – presumed widowed, imprisoned, enslaved, on the run from the law. Jamie always wanted to be a father, and spent most of his life believing that he never would be. He lost his first daughter when she was born stillborn, then lost his wife and unborn child. His years of loneliness makes the family he is able to find later in life all the more beautiful. As I said earlier, Jamie and Claire use their second chance at marriage as passionately and lovingly as they can – they use it parenting. In Voyager, when Claire returns to Jamie in her late 40s, she tells Jamie about Bree. But those years of lost childhood can not be returned. They do not consider having another child, but they immediately begin collecting their new “family.” One of the most important people in their lives is Ian, Jamie’s nephew. Jamie “cares for him as though he were [his] son” (Voyager 34). Ian goes to America with them in Voyager, and quickly his Auntie Claire and Uncle Jamie take the place of his parents. Fergus, their fostered son who Claire has not seen in 20 years, comes to America as well, along with his young wife Marsali. On their homestead in North Carolina, the Frasers settle with their growing family, and Fergus and Marsali’s children become Claire and Jamie’s grandchildren. When Bree and Roger join with their own family, Jamie gets a second chance at parenting.

Marsali is the daughter of Claire’s rival from when she first came through the stones. Laoghaire fiercely hated Claire and tried to have her killed in the first novel. Though Claire tries to be gracious, there is a sense of pride when Marsali quickly starts calling her “Mother Claire” and Jamie “Da.” Fergus and Marsali are family in every sense of the word, though there is no blood tie. Fergus was a French street orphan taken into Claire and Jamie’s home, but he never had a last name. The day he marries Marsali, Jamie gives him his name. “‘Fergus Claudel Fraser,’ he [Jamie] said, slowly and clearly. One eyebrow lifted as he looked at Fergus. He [Fergus] nodded slightly, and a glow rose in his face, as though he contained a candle that had just been lit” (52). Their relationship is a close one, and Jamie calls him mon enfant. Marsali and Claire also grow a close bond over the years, as do Bree and Marsali. Their sons Germain and Jemmy are best friends and cousins. The fact that neither Fergus nor Marsali are of any blood relation to the Frasers does not matter. One of the most touching scenes in the series is between Fergus and Jamie. “‘For a long time,’ [Fergus] said at last, ‘when I was small, I pretended to myself that I was the bastard of some great man. All orphans do this, I think. It makes life easier to bear, to pretend that it will not always be as it is, that someone will come and restore you to your rightful place in the world. Then I grew older, and knew this was not true. No one would come to rescue me. But then, then I grew older still, and discovered that, after all, it was true. I am the son of a great man. I wish for nothing more’” (Echo in the Bone 18).

Jamie and Claire also find a son in Roger, Bree’s husband. Roger is an orphan much like Claire, both his parents dead in WWII. He had no roots in his life, no family. When he met Claire and Bree in 1960, he fell in love with them and they family they represented. And he followed them 200 years across space and time to find a home there. Like Claire, the family he was brought into was like nothing he had experienced in his own time. During the years that Bree and Roger spend with their children in their own time, while their daughter recovers from heart surgery, Roger and Bree are talking about whether returning was the right choice. Roger says, “‘I couldn’t risk my own kids losing their father. It’s too important. You don’t forget having a dad.’” Bree asks, “‘I thought… you were so young. You do remember your father?’” “‘No,’” says Roger, ‘“I remember yours’” (19). The bond that grows between Roger and his in-laws is what eventually leads them to return to the more dangerous and primitive era of pre-Revolutionary War North Carolina. But the family that Jamie and Claire grow in the mountains of Colonial America is bigger than just their children and grandchildren. Bree rescues a young girl Lizzy and her aged father. They move onto the homestead and incorporate themselves into the family. Claire tries to help Malva, a girl with an abusive family. Jamie adopts Fanny, whose sister had recently died. They build a family and a community, a tight-knit group of people that has echoes of the Scottish clans that Jamie left behind in Scotland.

Although Jamie and Claire always welcome the needy into their family, there are many other examples of adoption throughout the series. In the second book, young Mary Randall’s husband dies and she marries his brother to make sure her baby has a father. That baby shows up later in the series as a friend of William’s. You find out that Roger’s great-great-great-great grandfather was a bastard, given up for adoption by his birth parents and raised by a poor family of farmers. Lord John Grey, step-father to William, was raised by a step-father himself. The series is full of displaced children who need parents, as well as displaced parents who need children. There are children who are readily adopted and loved, and parents who have to slowly learn to love. Outlander is the story of kinship. It is the story relatives who were born into the Fraser family, those who married into it, and those who were lucky enough to stumble upon it. The series explores how to love a child who is not yours, when Frank raises Bree. Likewise, it explores the pain of giving up a child you love to give them a better life.

When the first book opens, we meet a very young Roger being raised motherless by his uncle. It’s a small scene, almost forgettable, but it sets the stage for the rest of the story. Characters like Roger, Claire, and William, are orphaned by war and displaced in time, yet they are able to rebuild a life and a family by redefining kinship. Love can create a bond as strong as blood, and vows can make a family out of strangers. At the same time, Jamie and Claire’s wedding vows “blood of my blood, and bone of my bone” also represent the desire to further your own lineage through both physical love and parenthood. It’s a hope for the future, that your family traits will endure through generations. Quintessentially, it is the hope that someone, 200 years in the future, will be an echo of who you are. Outlander plays with the pressure of both of these desires – the desire for companionship, as well as the desire for a familial belonging – in a complex way. In that sense Gabaldon’s story is actually quite a relatable one, making the on-going epic a series that I believe will endure its own test of time.

* Citations mark chapter numbers, not pages.

- Gabaldon, Diana. Outlander. 1991. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. Dragonfly in Amber. 1992. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. Voyager. 1993. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. The Drums of Autumn. 1996. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. The Fiery Cross. 2001. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. A Breath of Snow and Ashes. 2005. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. An Echo in the Bone. 2009. Kindle.

- Gabaldon, Diana. Written in My Own Heart’s Blood. 2014. Kindle.

Sarah

Reblogged this on ❝ L'ISOLA CHE NON C'É ❞.

LikeLike